My Background with VR

I bought a VR headset, the Valve Index to be used tethered with PC and its dedicated graphics card, about 6 months ago. Since then, I’ve mostly used my headset for applications such as:

In particular, VRChat and Pavlov VR are the only “social” applications listed here. And in these, even though I was in online lobbies with many other people, the experience did not feel very social since I wasn’t outgoing enough to try and make friends with people in the short amount of time I was there.

I was not very impressed with social VR. In VRChat (which I will introduce in more detail in the VRChat section), there were a few times I came close to having an actual conversation with someone else, but without the pretense of knowing that we are trying to talk to each other, it was a little hard to start conversations. Sometimes, people would approach me and show me stuff, but they would leave just as quickly, and were usually with other people they were talking to primarily.

VRChat is also just a crazy place – it reminds me of early amateur YouTube. Almost everything is user-made, so every world has its own ad-hoc aesthetic and hacky interactive features. And, of course, the avatars. There’s a rediculously huge variety of user-made avatars. And as far as I can tell, moderation is pretty relaxed so its typical to run into giant monsters that cover your view and spin wildly, random characters that play music or recordings of lines from movies or TV shows, and most commonly of all extremely sexualized anime girls with each (sometimes clothed, sometimes not) boob larger than their head and with simulated elastic physics.

I also briefly tried RecRoom (which I will introduce in more detail in the section RecRoom) one time recently. I think its much less well-known than VRChat, so I hadn’t heard about it until then. Overall I was very impressed with the UX. The avatars and worlds were much more constrained than VRChat’s, so the performance was much more optimized and the experience overall much more organized. I attended a VR talent show that was pretty funny, although most of the contestants were middle-to-high-school kids singing badly singing pop songs (sometimes multiple consecutive contestants sung that same pop song…). I had a positive experience, but wasn’t exactly sure what I was interested in doing next. The games weren’t as fun as other VR games I already had.

Overall, it was a funny gimmick to see the early stages of social VR, but I only participated in social VR around 5 times during 6 months.

Giving Social VR another Chance

Listening the Meta and technology enthusiasts talk about the promises of social VR, I started to wonder if there’s something that I missed from my previous experiences. The main thing, I noticed, was vising a friend or some aquaintance that I could actually chat with persistently and have some benchmark to compare to (talking with them physically). I didn’t, however, go as far as to install Meta’s Horizon Worlds. But, given the positive results of the following experiment, I may be willing to try it once in the future.

I invited a friend, who will go by QMD in this article, who I talk with (via text) frequently online to join me in VR via his Oculus Rift S, the last model from the old Rift days for Oculus. We first met in VRChat for about 2.5 hours, and then in RecRoom for about 2.5 hours.

VRChat

VRChat hadn’t changed much since that last time I used it a few months earlier. But, it has certainly improved a lot over its lifetime.

For the uninitiated, VRChat is a free VR application where you can visit user-created private/public virtual worlds. You exist in these worlds as a configurable and user-created avatar of your choice. If you’ve never seen VR Chat before, I reccomend looking up a short YouTube video demonstration, which will instantly give a better idea that a textual description.

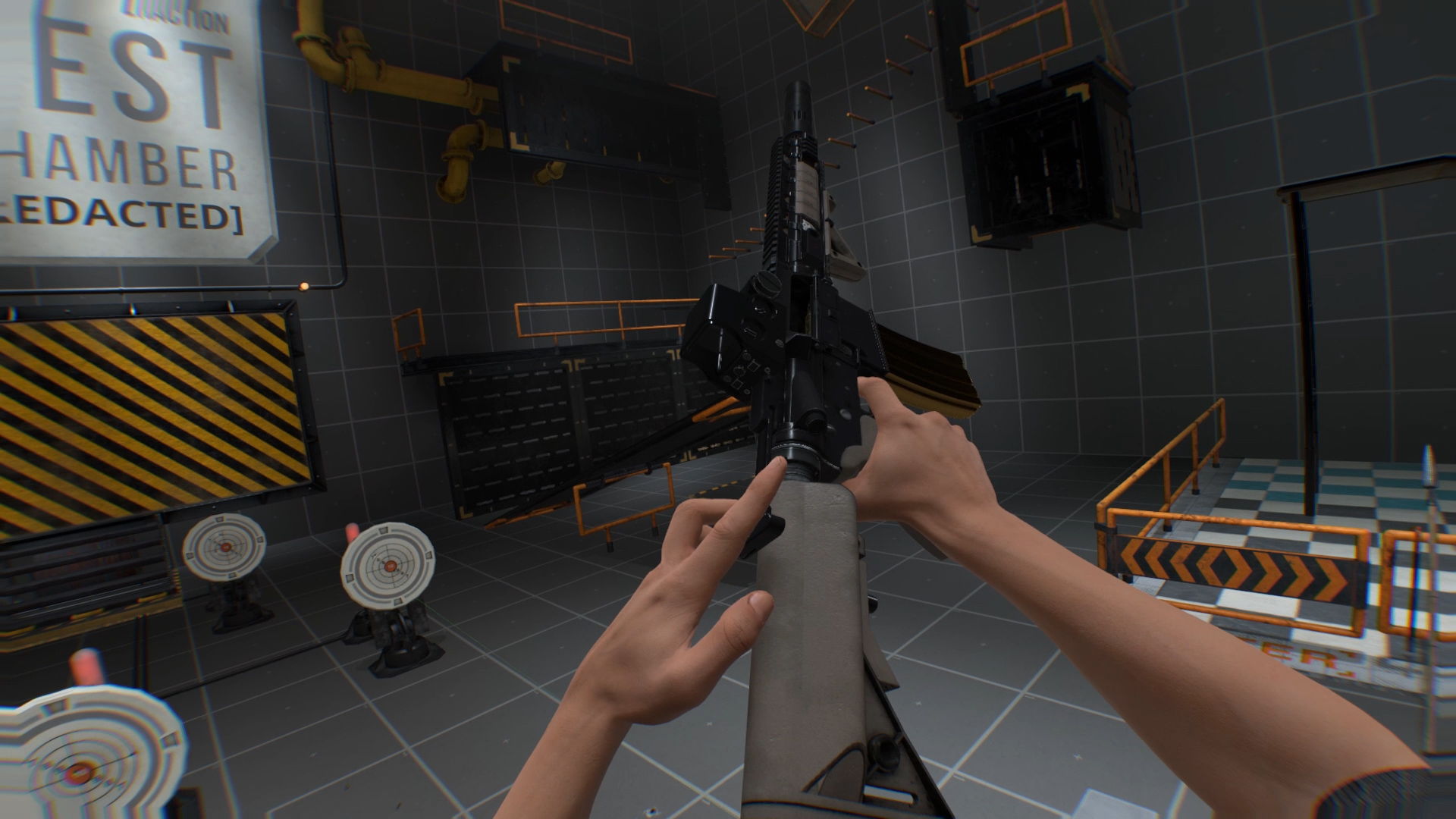

QMD and I donned anime girl avatar skins, which appeared to be the custom in most VRChat worlds. VRChat has these notable capabilities:

- Locations are organized into worlds. You can find world via a primitive search menu, or through hub worlds or other users that advertise certain worlds to you. Some worlds are static, intended for socializing or serving as a base to implement special activities on top of, and some worlds are designed to host a specific interactive game or other experience.

- Voice chat is distance sensitive; the volume of a person’s voice is proportional to how close they are to you.

- Your avatar tracks the movement of your head (via your headset) and hands (via your controllers or hand-tracking such as on the Oculus Quest 2). Additionally, most avatars have animations that make the character faux-lipsync, blink periodically, and move other limbs and attachments (e.g. legs, clothing, equipment, hair) to give the impression of physics.

- You can move and jump like in a typical 3D video game. This usually causes motion sickness however, so many newer users use teleport movement mode instead, which lets you use your controller as a pointer to choose where to teleport to, without inducing motion in your view.

To start, we explored a few different worlds and talked to some random users. Most of the users we met were male children – by the sound of their voices, in the age range 8-14. Most people used anime and cartoon avatars. In particular, using anime girl avatars was very popular, and QMD and I adopted this custom.

![]()

We met a particularly enthusiastic young user who guided us to a world that hosts a sort of avatar gallery, which was vast. While the avatars are all cartoonish, some of them were extremely sexual and sometimes even explicitly so. Many avatars had special emotes which are pre-rendered animations of the avatar doing a short expression such as dancing, clapping, jumping, smiling, shooting a laser gun, etc. The intention for some emotes seemed to be to truly emote i.e. communicate a certain expression. But, in our experience the emotes were exclusively used to show off something cool about the avatar.

One avatar I found particularly interesting was a squid puppet. The avatar was invisible except for a cute little cartoon squid attached to your right hand. So, you could control the squid as a puppet. While this avatar was cool, the problem with it was that you couldn’t really use it to communicate effectively with other people since it didn’t track the motion of your head or other arms, or have an animated mouth while you talked.

We explored a few other worlds to see what kinds of stuff people usually do in VRChat. There were some RP (role-playing) worlds, such as an RP Drama Court where people debated some joke criminal charges against a volunteered user. There were also many game-focused worlds such as a Tron-like laser disk game. Everything was user generated, so UIs were often very clunky and poorly explained, so you just kinda had to go around and tinker with things to see what happened. Most of the places we stayed had somewhere between 10 to 15 people. So, I’m guessing that around 15 people is the max number of users in most worlds. When the number of users overflows, the overflow users are typically sent to a parallel copy of the world.

Communicating with people was generally pretty difficult, but not impossible. You had to try hard to get people’s attention, when they were usually focused on talking with their current group of VRChat friends. There were few visual indications that someone you were trying to talk to was acknowledging you. Even if they turned to face you, there was no clear sense of eye contact. Additionally, some computationally intense worlds and avatars caused QMD and my programs to lag, which further hindered communication in a similar way to laggy video chat. However, almost always we found at least 1 person who was somewhat helpful or responsive when QMD and I wanted it. Suprisingly, we didn’t experience any harassment, joke-intended or otherwise.

Eventually, QMD and I settled down in a more “chill” world styled like an old Japanese village – that is, a static world meant for hanging out and talking rather than a game or other interactive experience. We went upstairs into what looked like a restaurant and sat next to a large window, which looked out over the town. It was very pleasant in comparison to what some might call the assault on the senses which was our experience so far. Still, there was someone else in the village that was transforming into a large dinosaur or something, which was distracting, so we configured earmuff mode which limited our hearing to just people within a few meters.

VRChat Review

QMD and I took physical and virtual seats to review our experience so far. How does our communication in VRChat compare to our physical interactions? For context, we both live in the USA, but far away from each other, so we usually only physically see each other once a year or so when we visit our hometown.

Attention. One on one, it was actually much easier to get a sense of whether the other person’s avatar was looking at you, or was paying attention to something else (such at looking out the window or interacting with a personal menu). The correspondence of the avatar’s head to your physical head was correlated enough that you could distinguish whether the other person was looking at the table between you or at you yourself, but since there is no eye tracking this accuracy was limited to head rotation. So, for example, it was hard to tell where exactly on the table the other person is looking since usually you just move your head in the general direction of the (normal-sized) table, and then move your eyes to pay attention to something specific on the table.

Natural Conversation. In audio and video calls, a common problem is accidentally talking over the other person since visual queues are impossible or harder to notice in time, especially with the introduced delay, in comparison to physical conversation. In VRChat, this effect is slightly mitigated by the availability of physical queues such as hand and head motion. When the other is talking while moving their hands, and then the make a finalizing gesture and stop talking, you know that you can start talking without a conflict. Or, when its ambiguous who should talk next, you can make a gesture towards the other person rather than say “you go” which could lead to another conflict. However, there is still a little lag (about the same as audio call, not as bad as many video calls). Overall, it seems like the additional body language provided by both head and hand movement is enough to noticably improve the sense of natural communication over video calling. But video has some other advantages as well, in particular the lack of facial expressions. Meta is working on this.

Avatar Projection. To some extent its still can be inherently hard to make it feel naturalnatural when your conversation partner is a sexy anime cat girl. But not all of that unnaturalness is bad, of course. Although avatars have some artistic details, they are hugely simplfied in comparison to the details of a person’s physical appearance. People choose an avatar in order to be funny, cute, or stylized for whatever preference. In order to have a casual conversation, QMD and I used simple avatars that didn’t have a lot of moving pieces so that we could focus on talking rather than messing around with emotes. Its fun to have your appearance abstracted in this way to something that you have full control over. When you go up to someone new, its straightforward to pre-judge them based on their appearance, and you don’t need to give a second though to how their physical body actually looks because for all intents and purposes that doesn’t matter in this context. Some of the users QMD and I talked to mentioned that they liked VRChat because it let them be social without experiencing anxiety, presumably for exposing their physical body and mannerisms to new people. In VRChat, the full control over your avatar’s appearance (as well as the ability to leave at any moment) provides a buffer between you and other people that can make it easier to be outgoing and experimental. My guess is that a big factor here is that it feels like you aren’t risking as much in a status game in these interactions, because of that buffer.

Shared Presence. A huge advantage of VR interactions compared to audio and video calls is the shared presence it provides you and your conversation partner. You each have your own perspective in the physical world, but you can experience that same things together. Thinking back to the time I spent with QMD in VRChat, it feels more like we visited a place rather than just playing the same game together. Above that, in contrast to playing non-VR video games together, the controlling a humanoid character in the VRChat worlds that the other person can react to contributes to a sense of bodily immeresion. What I was really left wanting, however, was the ability to share a computer screen, so I could show the other person something I looked up online, for example. What we really needed in VR was the equivalent of a tablet. I’m sure that something like this is possible, its just a matter of UI design. So, I’m very interested to see where that sort of feature becomes available.

RecRoom

After VRChat, QMD and I decided to try out RecRoom. I’ve used RecRoom briefly before, but QMD hadn’t.

RecRoom is similar to VRChat in the sense that it is also a free VR application where you can visit dev-created and user-created private/public virtual worlds. You exist in these worlds as a configurable avatar, but the avatar is very constrained compared to VRChat. The vanilla avatar body is very basic, and the accessories such as clothing and hair styles can only be acquired through an in-game shop that costs money (after converting it to in-game currency, of course).

QMD and I met in my dorm room, which is a private room that every user starts with. It has a white board with markers, mini basketball ball/hoop, water bottle (with crude particle effects when the water is poured out), a desk, a bed, and a mirror. So, an extremely luxurious dorm room. I was curious to see if the white board was effective for communicating written ideas to each other, and it roughly was. Drawing on it was basically as fine-grained as a real whiteboard. But, it was too small.

The aesthetic of RecRoom seems to be going for faux realism, where UI and game elements are depicted as if they were the physical analogues you’d see in the physical world. For example:

- the quick game menu is accessible by looking at your wrist as if you were wearing a watch

- doors which lead to other worlds are passed through by actually reaching out and opening the door

- accepting people into your party is performed by fist-bumping them

This definitely works in favor of an intuitive UX, and a somewhat immersive experience, but at times it does interfere with the efficiency of navigating menus and using things. Like, I would have preferred the whiteboard in my dorm room to be bigger, and the markers to be more fine-grained and pressure-insensitive.

RecRoom seems to have a focus on providing amateur in-game creation tools, such as the maker gun, which is a sort of advanced 3D pen that you can use in private areas. The structured you make can be moved around, but don’t have physics properties. QMD and I played around with this briefly while inside my dorm room.

Then, QMD and I went to the central hub world, the Rec Center, where we were again taken under the wing of a young-sounding user. He brought us to a horror-themed game world. The game was pretty boring, so we only tried it out for a few minutes before moving on. Over the next 2 hours we tried out paddleball, frisbee golf, paintball, bowling, and an escape room. The were all fairly impressive in how well-made they were, with paddleball, frisbee golf, and bowling standing out as very fun. The best thing we were looking for was something that we could do together while also chatting casually with each other. None of the games were particularly impressive as standalone games, but with a social aspect to them, they were perfect.

I noticed that, since our avatars were less interesting, we spent less time looking at each other’s avatars than just talking while passively doing other activities. This worked out pretty well, since its kinda awkward to, such as in a video call, just stare at the other person while you are having a conversation with them. In VRChat this was more normal because of how visually stimulating people’s avatars were.

Most of the worlds that we visited in RecRoom were dev-created, such as the paddleball and bowling. But, the escape room was definitely user-generated, which was apparent from its lack of polish and “minimalist” instructions. There definitely seems to be a lot of user-generated content in RecRoom, but we were satisfied enough with the dev-created worlds we tried for a few hours that we didn’t end up trying many of user-created ones.

RecRoom Review

Attention. One of the restrictions that comes with the avatars is that RecRoom’s developers decided to make the avatars simplified floating torsos with unconnected hands and a head. In particular, the avatars don’t have legs or arms. This didn’t turn out to limit expressiveness much in my opinion, since you don’t have direct control over your avatar’s legs and arms in VRChat anyways. The facial expressions of the RecRoom avatars aren’t very complicated either, although they do seem to respond to a few stimuli (e.g. if you throw something at an avatar, it will cause their face to briefly have a pained expression). It was harder to tell where each other were looking by looking at each other’s faces, since the eyes of RecRoom avatars are much less detailed (they’re basicallyj just stylized black dots). But, this never was an issue since the things we were interacting with were big enough that we didn’t need to worry about precisely tracking each other’s head movements – general head-facing direction was sufficient information.

Natural Conversation. This was basically the same as VRChat. Even with minimalist expressions of just simple faces on a head floating above a torso with floating hands, using body language while talking worked pretty much just as well as in VRChat. In fact, I think it usually worked a little better because the bodies of the RecRoom avatars are much easier to read than some of the weird VRChat avatars.

Avatar Projection. Since the avatars are also so similar, the appearance of your avatar doesn’t realy express that much detail about your choices. In fact, at one point QMD notified me that somehow I had put on a dress without realizing it. I didn’t really care, since the details of our avatars weren’t very important – I didn’t feel the compulsion to mess around with configuring my avatar like I did in VRChat.

Shared Presence. Since the environments felt more realistic and immersive than the VRChat environments, I could make more sense of them visually and intuitively, and therefore it felt much more like a shared place to visit with QMD than many of the VRChat worlds. Still, however, having tablets to use collaboratively inside of RecRoom would be a great feature which should be added as soon as possible.

Conclusions

What was new about this experience was that I shared it with someone that I have interacted with physically and in non-VR games many times before. In this way, I had an implicit benchmark to compare my VR interactions to like I haven’t had in my VR interactions with random people online.

With this in mind, overall, I was impressed with how much of the interactivity of physical interaction transfered to VR interaction. Of course, there are things that we could have done physically (such as get food) that are pretty much impossible to meaningfully transfer to VR, but there are also many things that we could do in VR that are impossible or very inconvenient to do physically, such as visiting interesting worlds and playing Tron laser disk battle, bowling, and paintball. Along these lines, I see hanging out in VR as a way to improve the experience of playing video games together. I would prefer to play mini golf, bowling, and similar games in VR with someone over getting together in person to do it, even if the person is close enough to me to feasibly join me for such an activity in person.

When it comes to the pure social experience of focusing on talking with someone, I was definitely impressed by the VR experience, but its still lacking in some critical aspects compared to the physical social expperience, and I’d say the lack of facial expressions is by far the biggest of these. I’m very interested in seeing how progress in the technology for that and its adoption goes, since I then that will be a huge improvement that could draw many more people in social VR, if its done well of course.

I’ll say this again as well – having a tablet in VR would be a huge benefit. So many times when I’m spending time with someone in person, we have a computer open or are sharing things from each other’s phones. Its so annoying to access your computer and phone while you’re in VR, and always a disappointment when you can’t share your view desktop or phone with other people. I’m not sure how this exactly should be implemented, but something like a mini desktop that you could spawn into the world would be a good start.

I see current social VR as good for socializing with friends that you don’t see regularly in person. In the near term future, it could be an ideal medium for audio-visual interactions such as podcasts, planning, and team meetings. I could easily imagine hosting a podcast in VR – maybe Yuta and I will try that someday. I also mention team meetings since it can be cumbersome to get several people to come to the same location to meet for an extended period that involves primarily sitting down around a table or at a whiteboard doing things you mostly prefer doing in your own workspace. But, meeting in person has proven, at least for the kinds of meetings I have, to have many benefits over video calling. My hypothesis is that much that is lost going from physical meetings to video calls is preserved by VR interactions.

Lastly, in retrospect, I feel like I had more fun in RecRoom than VRChat since it was easier to specifically focus on talking with QMD rather than getting distracted with complicated avatars and random bullshit happening all around us. There is definitely something lost there though, where VRChat feels more exciting and RecRoom feels more predictable. More generally, VRChat feels like it has much more content and much more variety of content overall, so I could see there being particular worlds I would be interested in enough to boot up VRChat specifically to visit, but none of the worlds I’ve seen so far qualify. Finally, if I was inviting someone to hang out with me in VR for the first time, I would choose RecRoom over VRChat pretty much every time.